One question stood out as the Missouri Supreme Court on Tuesday held its first oral arguments while social distancing, with lawyers and judges checking in on video feed and reporters and others listening to live audio.

The coronavirus pandemic led to the unique arrangement, and it wasnŌĆÖt perfect, but democracy and the cause of justice was served.

ŌĆ£Why hasnŌĆÖt the circuit attorney joined with the defendant in asking the governor for a pardon?ŌĆØ asked Judge Zel Fischer.

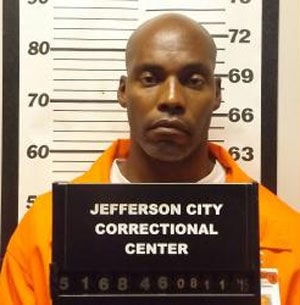

The question got to the heart of the legal wrangling in a case that involves the future of Lamar Johnson, but is really about the power of prosecuting attorneys.

People are also reading…

├█č┐┤½├Į Circuit Attorney Kimberly M. GardnerŌĆÖs new Conviction Integrity Unit produced a report that said Johnson, who was convicted of murder in ├█č┐┤½├Į in 1995, is innocent, and she wants a ├█č┐┤½├Į circuit judge to hold an evidentiary hearing on the merits of the case.

The judge, and Attorney General Eric Schmitt, have said Gardner has no right to ask that question under existing law and court rules, and that Johnson has other avenues through which to seek his release. The case has drawn national attention, with multiple amicus briefs ŌĆö most on GardnerŌĆÖs side ŌĆö filed by prosecutors, judges and legal scholars from around the country.

ItŌĆÖs folly to try to predict a court panelŌĆÖs ultimate decision based on the questions they ask during argument, but Fischer and his colleagues clearly will at least explore the possibility that there is another path to freedom for Johnson.

What about that pardon?

A former governor once described to me the moment in which a stateŌĆÖs chief executive ponders a pardon or commutation, or the decision to stop an inmate on death row from being executed, as the loneliest moment of a governorŌĆÖs tenure.

One person has that ultimate power, at the very end of the line of the judicial system, to allow his or her version of justice to prevail.

The current governor, Republica Mike Parson, has yet to use that power, which doesnŌĆÖt leave much confidence in that path for Johnson, should you believe, as I do, as Gardner does and as the Midwest Innocence Project does, that he was convicted in a horribly flawed trial.

Assistant Attorney General Shaun Mackelprang said that a ruling that would allow GardnerŌĆÖs office to seek a new trial on behalf of Johnson would ŌĆ£undermine confidenceŌĆØ in the judicial system.

ThatŌĆÖs only true if you accept that prosecutors donŌĆÖt have an obligation to undo the wrongs of the past.

But Mackelprang is correct that this case in many ways is about confidence in government.

ItŌĆÖs about the confidence that voters have in electing their own local prosecutors. ItŌĆÖs about confidence that the governor will use the powers granted to him. ItŌĆÖs about confidence that the legislature will pass laws that allow conviction integrity units to thrive, as other states have. ItŌĆÖs about confidence that when evidence of innocence is uncovered that the courts will find a way to seek justice.

ItŌĆÖs about confidence in the Missouri Supreme Court.

TuesdayŌĆÖs hearing, held amid unprecedented circumstances that have led to mass government shutdown, gave me confidence in the court.

HereŌĆÖs a body that is as tied to its old traditions as any other government body, maybe even more so, and it found a way to do its job weighing the life of a man who, his attorney said, was probably listening remotely at the Jefferson City Correctional Center just a few miles away.

IŌĆÖve spent a lot of time in the past several years writing about the Missouri Supreme Court, some good, some bad, but it is a body that nearly always represents to me the best of what government can be. Its seven members are a fair representation of Missouri ŌĆö four Democrats appointed by two different governors, three Republicans appointed by two different governors. The chief justice, George Draper, is an African American from ├█č┐┤½├Į, Fischer is a country lawyer from Tarkio. There are three women on the court.

Each of the judges got there the same way, competing among a panel of peers in a public interview process to make a list of three finalists determined by a commission of lawyers, judges and citizens. The governor then appoints a judge from that panel, and the judges on the court later stand for retention in a statewide election. This is , and it gives me confidence that the court, more than any other public body in the state, will work together to seek a solution based on the law, not politics.

We live in a time in which public confidence in government, and many of its major institutions, is failing. Some of that is by design, a deliberate attempt by some politicians to turn Americans against Washington or against the media or against their opponents. But when a pandemic sweeps the country taking lives and wreaking economic havoc, a little confidence in government would be a good thing.

I donŌĆÖt know how the court is going to rule in the Johnson case. But their presence, their process, their belief in consensus and shared governance, should be a guiding light as the Missouri Legislature, the governor and other public bodies do their business in these unprecedented times.

Republicans and Democrats, black and white, rural and urban, men and women: All deserve their seat at the table to have their voice heard, to help us climb out of the coronavirus morass.